The International Trade Blog Export Forms

USMCA Certificate of Origin Filling Software and How to Complete It

On: January 29, 2024 | By:  David Noah |

6 min. read

David Noah |

6 min. read

If you spend any time on the web (and who doesn't), I think you can relate to one of my pet peeves. It seems like every website I visit wants a unique password and username—one I have to either memorize or write down, so I can refer to it each time I log in.

If you spend any time on the web (and who doesn't), I think you can relate to one of my pet peeves. It seems like every website I visit wants a unique password and username—one I have to either memorize or write down, so I can refer to it each time I log in.

If you don’t have that information handy, or you’re working on a different computer (say, a laptop vs. your desktop), you have to reset your password.

It is such a tedious, annoying process that I finally bit the bullet and purchased Dashlane. The program keeps track of all my passwords for me, so I don’t have to remember (or look up) each one, every time.

It’s reliable. It’s secure. It’s easy to use. And it’s saved me so many headaches compared to the way I used to do it.

You get the same benefits from using our Shipping Solutions export documentation and compliance software, especially when you’re creating certificates of origin like the USMCA Certification of Origin (COO).

The Best Way to Create Your Certificates of Origin

Unlike many export forms that need to be created each time you have a shipment, many companies create a blanket USMCA COO for their customers once a year. These certificates of origin indicate exactly how your products qualify for preferential treatment.

Shipping Solutions software simplifies the process of creating these certificates. Each time you create a certificate of origin, the information is stored within the software. Depending on how often you create a USMCA COO—whether once a year or more frequently—you will have a record of the certificates you’ve created.

The next time you create one, you can easily copy pre-existing information to a new record, change the date and review the information for accuracy to create your new USMCA COO. This ensures you always use the correct information when you’re filling out the form.

Shipping Solutions software saves you lots of time creating certificates of origin (and all your other forms, too) and spares you costly errors. Don't just take my word for it. Schedule a free, private online demo of the software.

If you’re not ready to try the software or want to learn more about how to complete the USMCA Certificate of Origin, keep reading.

How to Complete the USMCA Certification of Origin

After more than 25 years of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Canada, Mexico and the United States signed a new free trade agreement between the three countries called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) that went into effect on July 1, 2020, and replaced NAFTA.

The new agreement modernizes NAFTA and addresses topics that were less relevant when NAFTA went into effect in 1994, such as e-commerce and the flow of international data. Check out the blog post, NAFTA vs. USMCA, for more details about the changes.

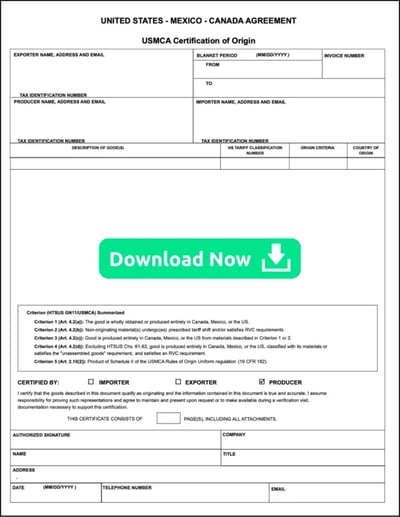

While there is no longer an official certificate of origin form, whichever party is certifying that the goods meet the rules of origin must provide, at minimum, certain data elements as outlined in the agreement to support the claim. That information can be provided on the invoice or on a separate attached document—a USMCA Certification of Origin.

While there is no longer an official certificate of origin form, whichever party is certifying that the goods meet the rules of origin must provide, at minimum, certain data elements as outlined in the agreement to support the claim. That information can be provided on the invoice or on a separate attached document—a USMCA Certification of Origin.

Only importers who possess valid certification of origin can claim this preferential tariff treatment. This certification summarizes the claim that goods qualify as originating and should therefore receive preferential tariff treatment.

Exporter Name, Address and Email

Complete with the full legal name, address, country, email address and tax identification number of the exporter.

Please Note: The legal tax identification number depends on the country:

- For U.S. exporters/importers, this number is the employer identification number assigned by the Internal Revenue Service. If you don't have such a number, you may use your social security number.

- For Canadian exporters/importers, use the employer number assigned by Revenue Canada or, if not available, the importer/exporter number assigned by Canada Customs.

- For Mexican exporters/importers, use the federal taxpayer’s registry number (RFC).

Blanket Period

Complete this field if the certificate covers multiple shipments of identical goods described in the Description of Good(s) that are imported into a USMCA country for a specified period of up to one year (blanket period). From is the date upon which the certificate becomes applicable to the good covered by the blanket, and it may be prior to the date of signing this certificate.

Invoice Number

If the USMCA Certificate is relevant to a single shipment instead of multiple shipments within the designated blanket period, the agreement recommends but does not require that the party certifying the goods include the invoice number for this shipment.

Producer Name, Address and Email

Complete with the full legal name, address, country, email address, and legal tax identification number of the producer. This is no longer a required field unless the producer is the party certifying that the goods qualify under the terms of the USMCA.

Importer Name, Address and Email

State the full legal name, address, country and legal tax identification number of the importer. Since the importer is the party making the claim for preferential duty rates, the importer must be included.

Description of Good(s)

Provide a full description of each good. The description should be sufficient to relate the good to the invoice description and the Harmonized System (HS) description of the good. It is the exporter's responsibility to ensure that the description of goods covers only those goods that qualify under the rules of origin.

HS Tariff Classification Number

The HS or "Harmonized System" is used by customs authorities around the world to identify the duty and tax rates for specific types of products. For each good identify the HS classification to six digits.

Origin Criteria

This field identifies the origin criterion used as the basis of preferential treatment. The criterion cited in this field is the foundation of the importer's claim. The Origin Criteria options are shown in the chart below.

Country of Origin

Identify the country of origin. It must be US, MX or CA to qualify for the USMCA.

Certified By

Indicate which party to the transaction is certifying that the goods qualify under the USMCA rules of origin and the statement required on the form:

I certify that the goods described in this document qualify as originating and the information contained in this document is true and accurate. I assume responsibility for proving such representations and agree to maintain and present upon request or to make available during a verification visit, documentation necessary to support this certification.

Under the USMCA, the party can be the importer, exporter or producer.

Certifier Information

These fields must be completed, signed and dated by a representative of the party certifying that the goods qualify. The person who signs this declaration must be knowledgeable about the company’s products and have authority to commit the exporter. Custom authorities may question certification signed by clerks and others in the company who are neither knowledgeable nor authorized to represent the exporter.

If the party that completes and signs the certificate of origin has reason to believe that the certificate contains incorrect information, they have 30 calendar days to notify in writing all persons to whom the certificate was given of any changes that could affect the accuracy or validity of the certificate.

The rules of origin are very complex, and you should not make assumptions that your products qualify for duty-free status under USMCA (or any of the free trade agreements) without carefully reading the rules. Before a party completes a certificate of origin, they must be certain that their products meet these standards.

Additional Resources

- How to Qualify for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) whitepaper

- Classifying Your Products for International Trade whitepaper

- USMCA: The Modernized NAFTA webinar

Like what you read? Join thousands of exporters and importers who subscribe to Passages: The International Trade Blog. You'll get the latest news and tips for exporters and importers delivered right to your inbox.

This article was first published in April 2018 under the name NAFTA Certificate of Origin Filling Software and How to Complete It and has been updated to include current information about the USMCA, new links and subtle formatting changes.

About the Author: David Noah

As president of Shipping Solutions, I've helped thousands of exporters more efficiently create accurate export documents and stay compliant with import-export regulations. Our Shipping Solutions software eliminates redundant data entry, which allows you to create your export paperwork up to five-times faster than using templates and reduces the chances of making the types of errors that could slow down your shipments and make it more difficult to get paid. I frequently write and speak on export documentation, regulations and compliance issues.

.webp?width=763&height=852&name=CTA%20-%20How%20to%20Qualify%20for%20a%20Free%20Trade%20Agreement%20(FTA).webp)